When will the next general election be held and what kind of impact will the pandemic and Brexit have on the choice of timing, writes Bremain Chair Sue Wilson MBE for Yorkshire Bylines.

There has been much speculation over recent weeks and months about the timing of the next general election. Scheduled to take place in 2024, there are many factors that could influence the government’s decision – to wait or not to wait. Obviously, when given the choice, any government would choose the timing based on their assessment of their chances of success.

With any election, the time of the year can be a significant factor, as turnout can be appreciably affected by the weather. A cabinet source recently told The Mirror, “Labour struggles to get their people out more than we do which gives us an advantage”. However, there are many other factors to be considered, especially in the wake of Brexit and the pandemic.

Fixed Term Parliament Act

The reason the government can even consider holding the next election before 2024 is due to the repealing of the Fixed Term Parliament Act. In March 2021, a joint committee of MPs and peers concluded that the act was “flawed and would require major amendment even if it were to be retained”.

The government’s intention was clear, the committee said – “to return to the system in place before the 2011 Act”. Committee chair, Lord McLoughlin said the “bill means the Monarch may grant a general election on the request of the prime minister of the day”. The dissolution and calling of parliament bill is currently at second reading stage in the House of Lords. It is making swift progress towards giving the government the freedom to call an election when it sees fit.

Boundary changes

According to the Boundary Commission for England, revised proposals on boundary changes will be published, and a four-week consultation process will be conducted “late 2022”. A final report, including recommendations, will be published in June 2023.

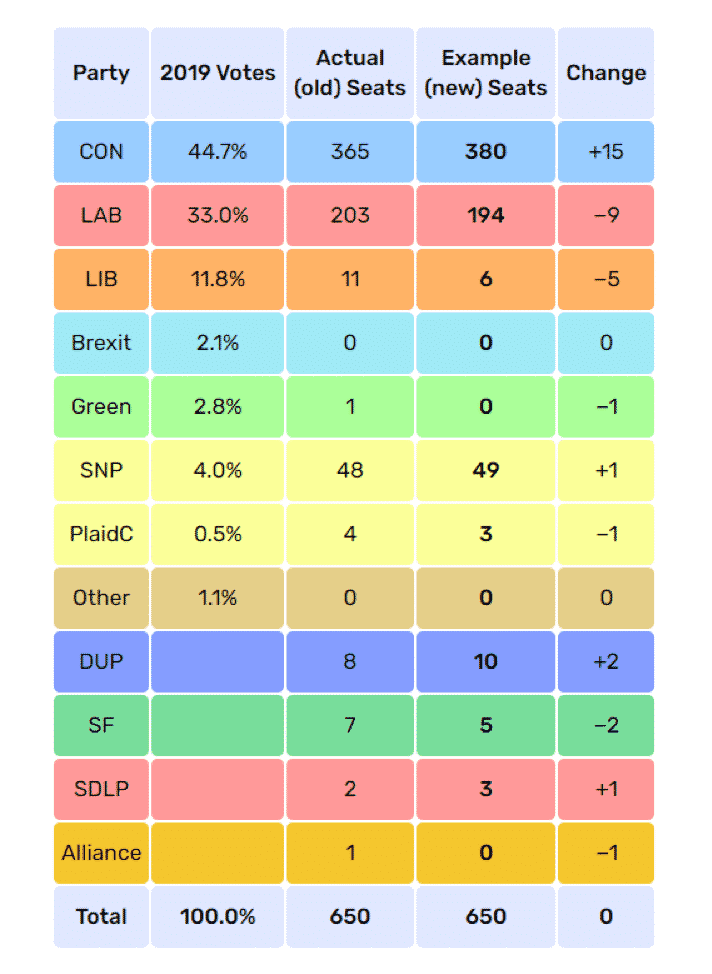

One school of thought is that the government will wait until after the boundary changes come into effect. The reason being that, if the 2019 election had been conducted under the new boundary arrangements, with every voter voting the same way, the Conservative Party would have gained 15 seats, and Labour would have lost a further nine. Even if voting patterns were to change, the Financial Times concluded that the government would gain ten new seats following boundary adjustments.

However, others have argued that the government will call an election before the changes come into effect while existing boundaries remain. Crestview Strategy’s vice president, Nicholas Varley, argued that to call an election after the boundary changes would be “an act of lunacy” on the government’s part. He argued that it takes years for MPs to “build their reputation with local voters and a change in boundaries would mean years of hard work by MPs in this parliament are deemed worthless”.

“What will be causing sleepless nights is the idea that no one in the campaign team at Conservative Central Office, or even Conservative Members of Parliament themselves, can be certain of which voters will be voting in which constituency in an impending general election. If you do not know who your electorate is how can you run a campaign? And, we aren’t just talking about not knowing the electorate in a handful of constituencies, we are talking about 90 percent of constituencies looking different.”

The Brexit effect

Brexit could be a significant factor in any decision re the timing of the next election, and the government would need to be looking in two directions simultaneously. Firstly, there’s the damage already being caused by Brexit, and we haven’t even seen the worst of that yet.

Any perceived Brexit bounce that may have come from the government getting Brexit ‘done’ has surely now dissipated. If the election was to come too soon, the issues of supply chain problems, fuel shortages, empty shelves, lack of drivers, etc. etc. will be fresh in the public memory. Even if they believe the government line that those issues are due to covid, not Brexit, it’s same problem – the government has mishandled both in spectacular fashion.

Secondly, there’s the future of Brexit – the ongoing negotiations and severely troubled relationship with the EU. Not only is Brexit not done, but if the result of the latest UK posturing results in a trade war, then the picture could look considerably worse. In which case, a delay might be the best course of action for the government, in order to put as much space between themselves and the damage as possible.

That’s before they even factor in the renegotiations that are due to take place in 2025 when the trade and co-operation agreement is up for review. Assuming, of course, that it hasn’t been torn up altogether by then.

Then there are the promised Brexit benefits that have failed to materialise. The much-heralded new deal with Australia has not, as previously suggested, been signed sealed and delivered. Even the rollover EU deals are proving problematic, as the devil in the detail was overlooked. The uplands are not looking so sunny

… and then there’s covid

With regard to covid, a number of factors must surely be considered. Firstly, any capital the government may have gained from the so-called vaccine bounce has almost certainly now been lost. Then there’s the forthcoming covid inquiry that will likely reveal significant government mistakes – including many that could have been avoided and saved lives. The billions spent – in many cases wasted – will not go unnoticed, and again, the government may well want to put some distance between the fallout and the next public vote.

As for the current state of play, the UK is falling behind its neighbours in tackling covid. Despite appearances to the contrary in some quarters, covid has not gone away. The number of new cases is growing out of all proportion to similar countries, with daily case levels dangerously close to 50,000. Add in all those bereaved families and that’s a lot of people with a huge axe to grind, not even mentioning those still waiting for any sign of ‘levelling up’.

The view from Westminster

The recent government reshuffle has only added to speculation in Westminster that the PM would call an early election. However, when asked recently to comment on the possibility of a 2023 election, Conservative Party chair Oliver Dowden refused to be drawn. He recently told Sky News, “The PM has told me to make sure that the Conservative Party machine is ready to go for an election whenever it comes”. He added, “It’s not my job to call an election. We know full well that the usual electoral cycle would take us through to 2024 but that’s entirely up to the prime minister”.

In response, government figures played down Dowden’s comments, telling The Times that Boris Johnson would be more likely to wait until 2024 when the next general election is officially due.

As for the opposition, Labour strategists are increasingly considering the possibility that Johnson might even go for an election as early as spring next year. The thinking being that the government will want to act before the tax rise of businesses and workers – aimed at providing additional funding for the NHS – comes into play in April 2022.

At the recent Labour Party conference, the shadow foreign secretary, Lisa Nandy, said the party was ready for an expected election in 2023. “We could be in power in 18-months’ time. Never believe it’s not possible”.

What do the punters say?

Although the odds vary, all gambling sites agree that an early election is becoming increasingly more likely. Smarkets betting exchange said, “The chances of it being held in 2023 have continued to rise, now up to around 38 percent and that seems to make a lot of sense”.

The odds on a 2024 (or later) election range from Oddschecker on 4/7 (a 63 percent probability) to Gambling.com on 3/10 (a 77 percent probability). The odds on a 2023 election range from Oddschecker on 6/5 (a 45 percent probability) to Gambling.com on 7/2 (a 28 percent probability).

With the UK paying off the pandemic deficit, Brexit damage becoming more obvious and the impact of boundary changes, there is much to consider when making this decision. Johnson has already made it clear he wants to serve as PM longer than Thatcher. Of course, that decision will not just be down to the voting public, but also down to his own party. Trust is at an all-time low and needs to be earned. Recent events have opened the public’s eyes to the lies, the cronyism and the waste of life and taxpayers’ money.

In 2023–2024, Britain will hit record borrowing according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation. Both organisations predict that ahead of the next election, there will be enormous pressure on the government to balance the books.

So, from wherever you are standing, the government has some major decisions to make about whether it will be viewed more kindly sooner, or later. An election in 2023? I wouldn’t put my money on it just yet. But then I wouldn’t bet against it either!

Definitely not so he can pretend there's been better growth in the economy next year & use that to put in tax cuts in the Autumn 2022 budget, in case of an election in 2023.

Definitely not.

They'd never play politics with the economy.

They're a 'safe pair of hands' after all…— (Social) Liberal Leigh🕷️🇪🇺🇬🇧 #FBPE #FBPPR 🔶 (@Liberal_Leigh) October 16, 2021